Urich Lawson

On Thursday, research publisher Science announced that all of its journals will begin using commercial software that automates the process of detecting improperly manipulated images. This move comes many years after we realized that the shift to digital data and publishing had made it easier to commit research fraud by altering images.

Although this is an important first step, it is important to recognize the limitations of the program. Although it will be able to detect some of the most egregious cases of photo manipulation, enterprising scammers can easily avoid getting caught if they know how the software works. Which, unfortunately, we feel compelled to describe (and to be fair, the company that developed the program does so on its website).

A fascinating scam and how to catch it

Much of the image-based fraud we've seen arises from a dilemma many scientists face: It's not a problem to run experiments, but the data they generate is often not the data you want. Perhaps only controls work, or perhaps experiments produce data that are indistinguishable from controls. For non-ethical people, this is not a problem because no one but you knows which images come from which samples. It is relatively easy to present images of real data as something they are not.

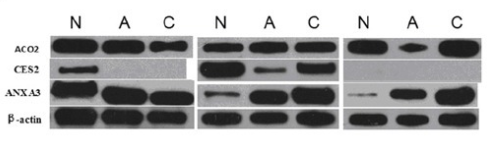

To illustrate this, we can look at the data through a procedure called a Western blot, which uses antibodies to identify specific proteins from a complex mixture that has been separated according to protein size. Typical Western blot data looks like the image on the right, where the darkness of the bands represents proteins present at different levels under different conditions.

A Western blot like this, with so many individual images removed from their original context, makes it easy to commit research fraud.

Note that the bands are relatively featureless and are cropped from larger images of the raw data, disconnecting them from their original context. It is possible to take bands from one experiment and correlate them in an image of a completely different experiment, fraudulently generating “evidence” that does not exist. Similar things can be done with graphs, cell images, etc.

Because data is difficult to obtain and scammers are often lazy, in many cases, the original and fraudulent images are extracted from the data used for the same paper. To cover their tracks, unethical researchers often rotate, zoom, crop, or change their brightness/contrast images and use them more than once in the same paper.

Not everyone is that lazy. But such image recycling is remarkably common and perhaps the most frustrating form of research fraud. All the evidence is in the paper, and it's usually easy to see once you point to it. But it can be very difficult to detect in the first place.

The “spot in the first place” challenge is why science turned to it A service called Proofig To make it easier to detect problems.

“Infuriatingly humble alcohol fanatic. Unapologetic beer practitioner. Analyst.”