Subscribe to CNN’s Wonder Theory newsletter. Explore the universe with news about amazing discoveries, scientific advances, and more..

CNN

—

The Stonehenge altar stone, which lies at the heart of the ancient monument in southern England, was likely transported more than 435 miles (700 kilometers) from what is now north-east Scotland nearly 5,000 years ago, according to new research.

The results of a new study published Wednesday in the journal natureoverturning a century-old idea that the Altar Stone originated in present-day Wales. The Altar Stone, the largest of the bluestones used in the construction of Stonehenge, is a thick block weighing 13,227 pounds (6 metric tons) and stands in the centre of the stone circle.

“This stone has travelled an incredible distance – at least 700 kilometres – and is the longest recorded journey of any stone used in a monument of this period,” Nick Pearce, a professor in the Department of Geography and Earth Sciences at Aberystwyth University in Wales, said in a statement. “The distance travelled is astonishing for the time.”

The study’s authors said the research directly addresses one of Stonehenge’s many mysteries, and also opens up new avenues for understanding the past, including links between Neolithic inhabitants who left behind no written records.

Stonehenge began construction as early as 3000 BC, and was completed in several stages, according to researchers. The altar stone is believed to have been placed inside the central horseshoe during the second construction phase around 2620 to 2480 BC.

The study’s authors wrote that the discovery of the stone’s origin suggests that ancient Britain and its citizens were more advanced and capable of transporting large stones, perhaps by sea.

Substantial research has focused on the types of stone used to assemble the famous circle in Wiltshire over the years, and previous analyses have shown that bluestone, a type of soft sandstone, and siliceous sandstone blocks called sarsens were used in the construction of the monument. The monument is located on the southern edge of Salisbury Plain, which has been inhabited for around 5,000 to 6,000 years.

The sarsen stones came from the West Woods area near Marlborough, about 15 miles (25 kilometres) away, while some of the bluestones originated from the Presley Hills area in west Wales, and are thought to be the first stones placed at the site. Researchers have identified the altar stone with the bluestones, but its origins have remained a mystery until now.

“Our discovery of the origins of the altar stone highlights a significant level of community coordination during the Neolithic and helps paint a fascinating picture of prehistoric Britain,” Chris Kirkland, co-author of the study and professor and head of the Mineralogical Systems Timescales Group at Curtin University’s School of Earth and Planetary Sciences in Australia, said in a statement.

“Moving such large cargoes overland from Scotland to southern England would have been a huge challenge, suggesting the possibility of a sea-based shipping route along the coast of Britain. This implies long-distance trading networks and a higher level of societal organisation than is widely thought to have existed during Neolithic Britain.”

To better understand the origin of the altar stone, researchers analyzed the age and chemistry of mineral grains from fragments of the stone itself.

Analysis revealed grains of zircon, apatite and rutile within the pieces. The zircon was dated to between 1 billion and 2 billion years old, while the apatite and rutile grains were dated to between 458 million and 470 million years old.

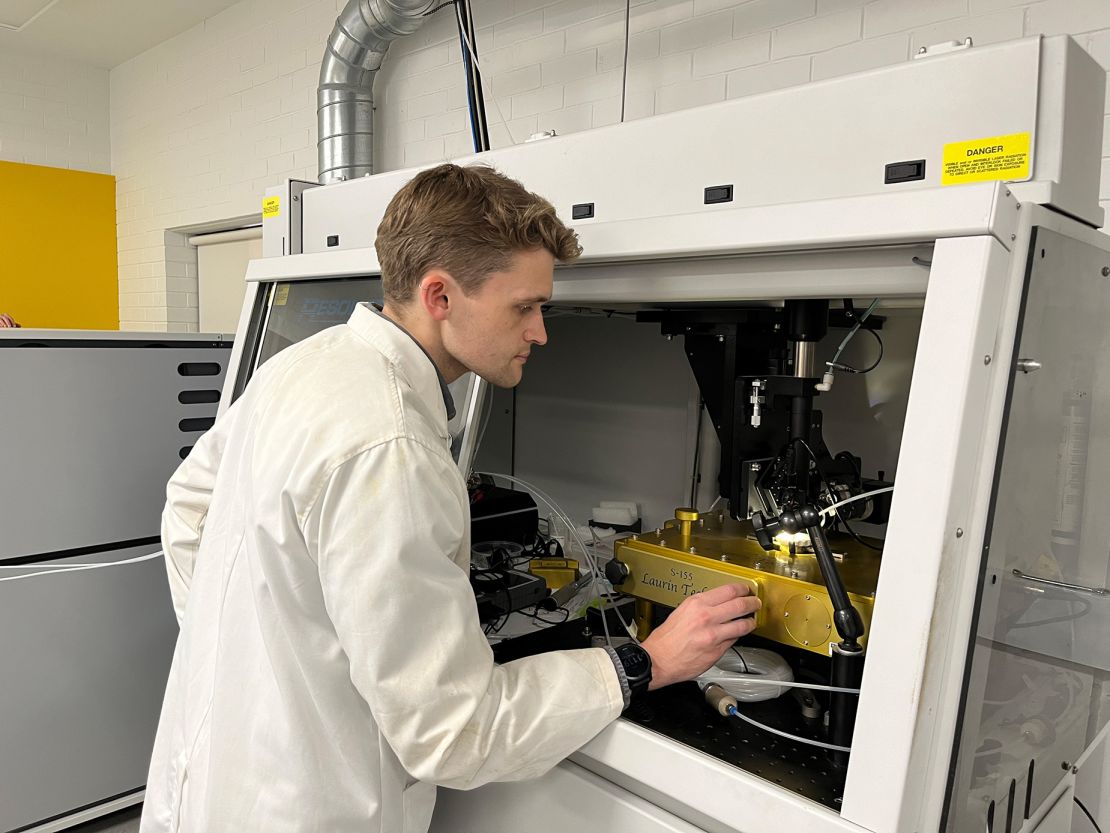

The team used age analysis of the mineral grains to create a “chemical fingerprint” that could be compared to sediments and rocks across Europe, said lead author Anthony Clarke, a PhD student in the Timescales of Mineral Systems Group at Curtin’s School of Earth and Planetary Sciences. The grains best match a group of sedimentary rocks known as the Old Red Sandstone found in the Orcadie Basin in north-east Scotland, which is very different from the rocks found in Wales.

“The findings raise fascinating questions, given the technological limitations of the Neolithic, about how such a massive stone could have been transported over vast distances around 2600 BC,” Clark said.

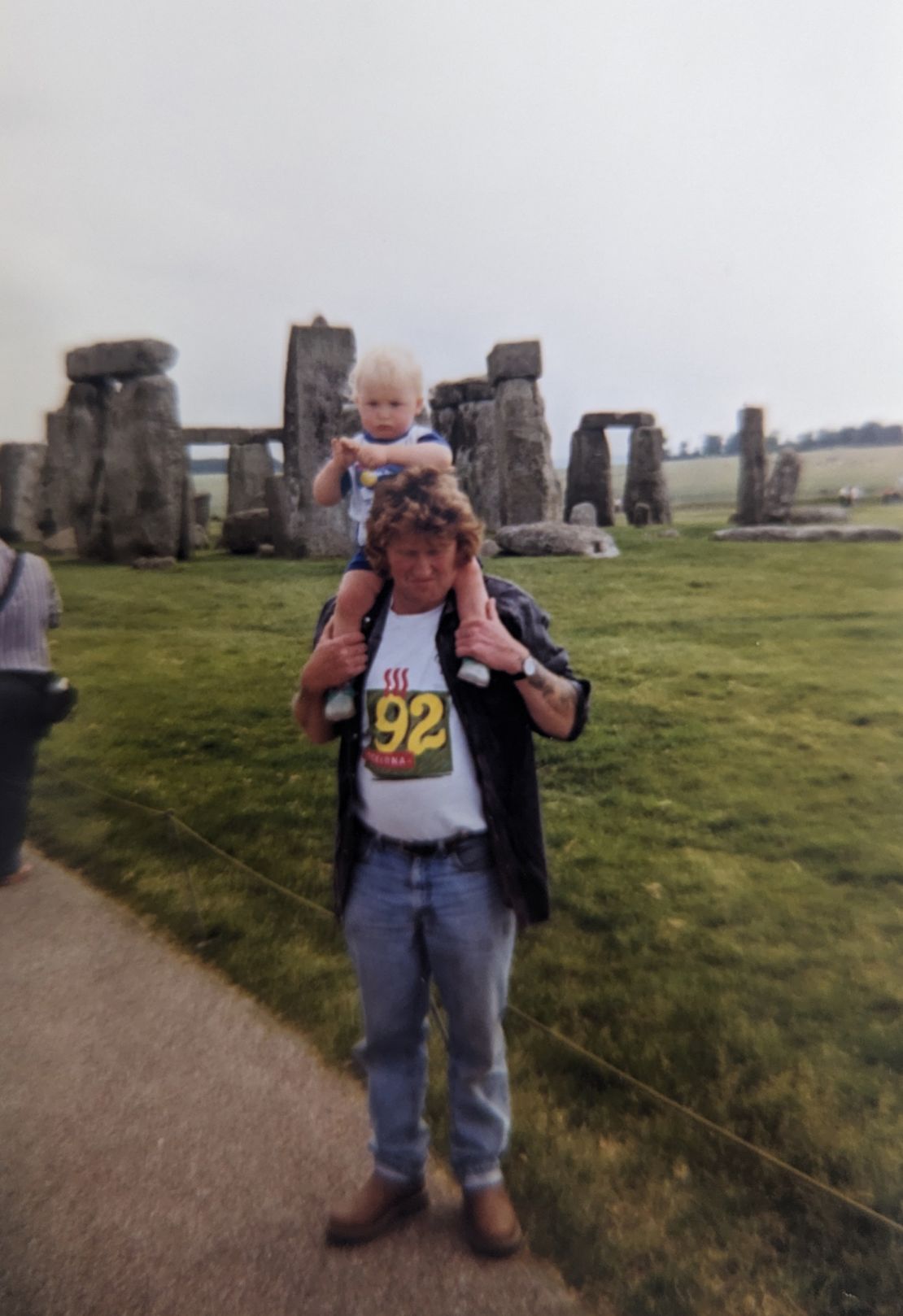

The discovery was also a personal one for Clarke, who grew up in the Preseli Hills in Wales, the point of origin for some of the Stonehenge stones.

“I first visited Stonehenge when I was “When I was 25 and now when I am 16, I came back from Australia to help make this scientific discovery happen – I can say I completed the stone circle,” Clark said.

But confirming that the altar stone originated in what is now Scotland raises many new questions.

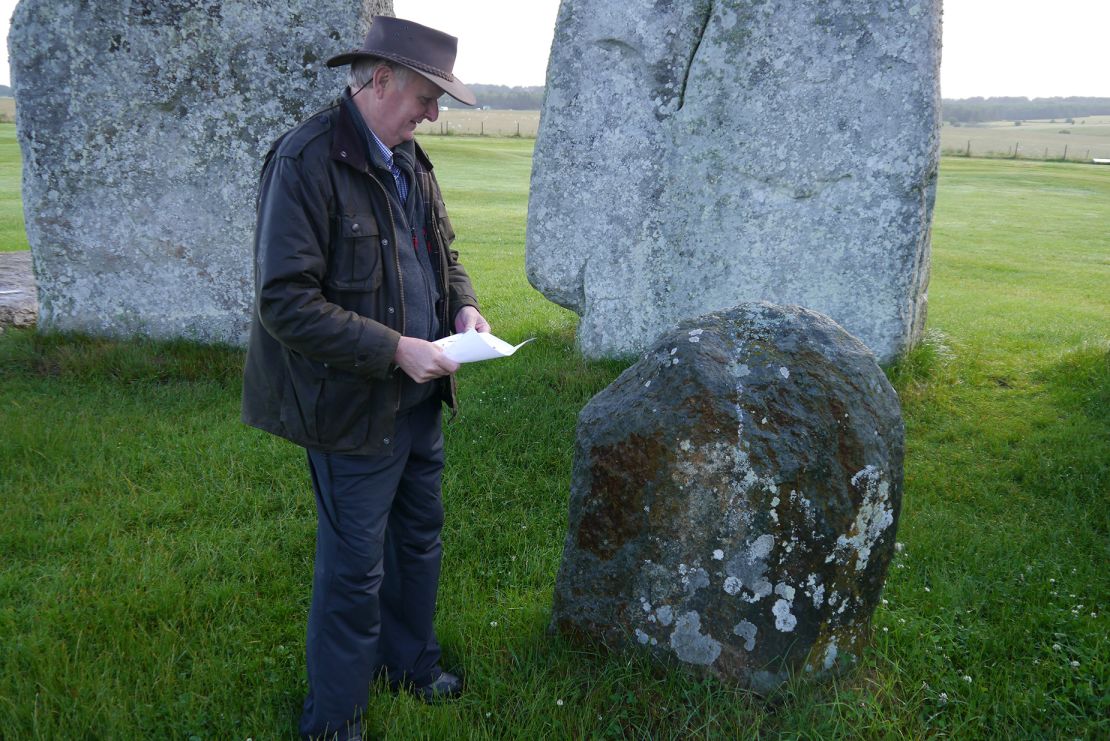

“It is exciting to know that our chemical analysis and dating work have finally solved this great mystery,” Richard Bivins, an honorary professor in the Department of Geography and Earth Sciences at Aberystwyth University and co-author of the study, said in a statement. “The search will continue to determine exactly where the altar stone came from in north-east Scotland.”

“This is a great result,” said Joshua Pollard, a professor of archaeology at the University of Southampton. Pollard was not involved in the research.

“The science is good, and this is the team that succeeded in getting the smaller Stonehenge bluestones using a very complex set of techniques,” Pollard said.

Today, the altar stone lies broken on the ground, and on top of it rest two stones from the collapsed Great Trilithon. A trilithon is a pair of vertical stones with a horizontal stone across their tops. The horseshoe shape at Stonehenge contains five trilithons, but the Great Trilithon was aligned with the axis of the winter solstice, so on the winter solstice the sun appeared to set between the two stones.

But researchers question whether the altar stone ever stood, as well as what purpose it once served.

“One suggestion is that the stone served as a testament to the dead, so Neolithic people built stone circles as part of their ritual to respect their ancestors,” Bevins said.

Bullard referred to the altar stone as “somewhat of an anomaly, lying in what should be the most sacred part of the space within the monument.”

But how exactly did the massive altar stone get to Salisbury Plain in the first place?

The study authors said Britain at the time was covered in forests and other impassable terrain, which would have made it very difficult to transport the stone by land. But Clark said a sea route would have allowed for shipping.

“While it looks amazing, Stonehenge itself is an amazing monument,” Pollard said. “It increasingly seems as though the stones are drawn from sources that go back to the ancestors of those who built Stonehenge – it’s a kind of condensation of historical genealogical stories into one place.”

There are other examples of animals, objects and stones being transported, suggesting that goods may have been shipped across open water during the Neolithic, the researchers wrote in the study. Stone tools have been found quarried across Britain, Ireland and continental Europe, including a large stone grinding tool found in Dorset that came from what is now central Normandy.

There is also evidence that the sandstone blocks were transported by rivers in Britain and Ireland.

“While our new experimental research was not intended to answer the question of how it got there, there are clear physical barriers to transport by land, but the journey would have been arduous if it had been by sea,” said Pearce. “There is no doubt that this Scottish source shows a high level of societal organisation in the British Isles during this period. These findings will have huge implications for our understanding of Neolithic societies and their levels of communication and transport systems.”

The authors agreed that some questions about Stonehenge may never be answered.

“We know why many ancient monuments were built, but the purpose of Stonehenge will forever remain unknown,” Clarke said. “So we have to turn to the rocks. It’s an eternal mystery.”

“Infuriatingly humble analyst. Bacon maven. Proud food specialist. Certified reader. Avid writer. Zombie advocate. Incurable problem solver.”